Beta burst dynamics in Parkinson's disease OFF and ON dopaminergic medication.

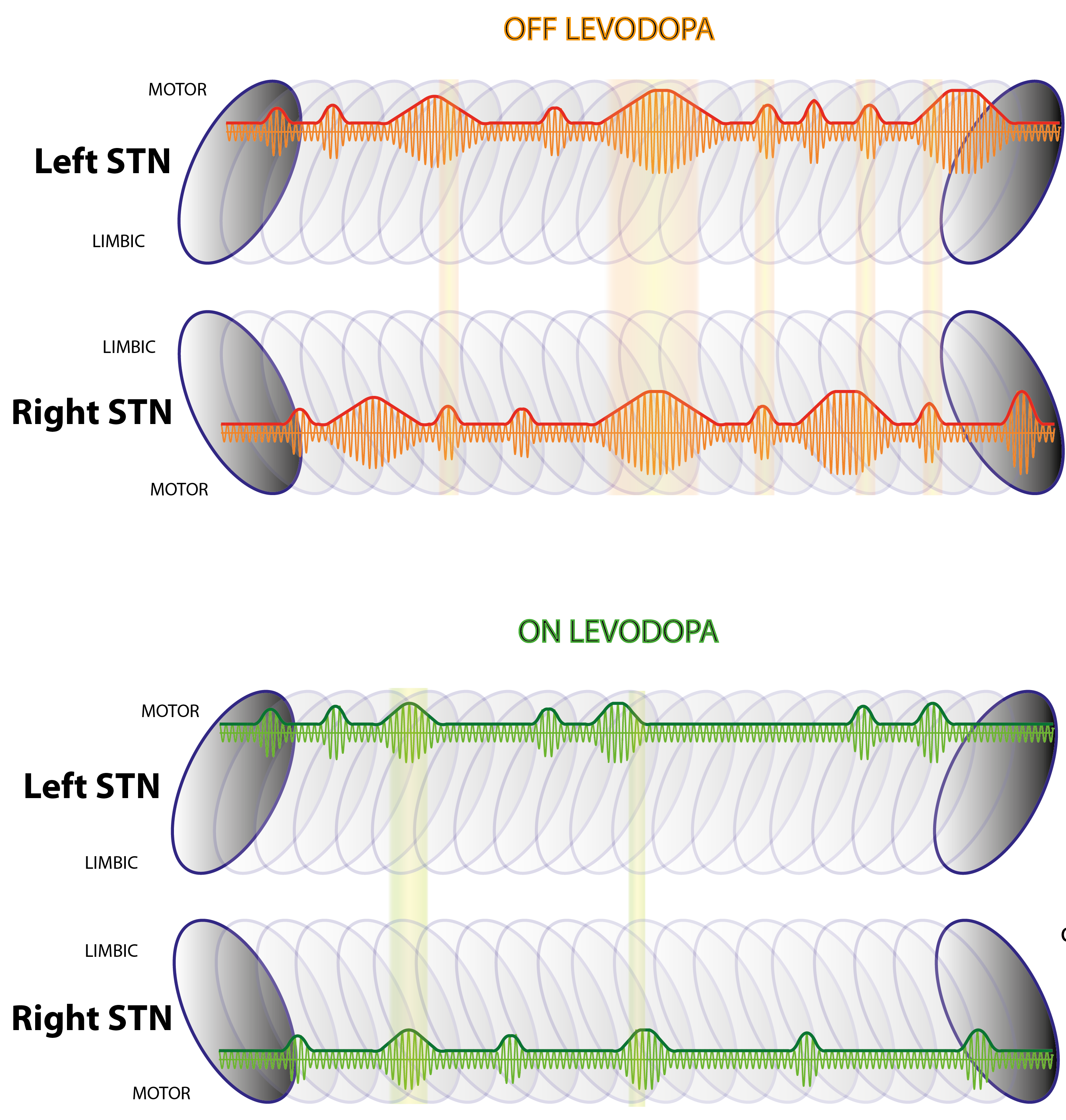

Here, we show that pathological brain waves tend to come in long bursts in people with Parkinson’s disease, and that a burst at one site in the brain circuits controlling movement is likely to be associated with bursts elsewhere in the movement circuits. The duration and spread of these bursts is governed by dopamine, a chemical messenger that is deficient in Parkinson’s.

Exaggerated basal ganglia beta activity (13-35 Hz) is commonly found in patients with Parkinson's disease and can be suppressed by dopaminergic medication, with the degree of suppression being correlated with the improvement in motor symptoms. Importantly, beta activity is not continuously elevated, but fluctuates to give beta bursts. The percentage number of longer beta bursts in a given interval is positively correlated with clinical impairment in Parkinson's disease patients. Here we determine whether the characteristics of beta bursts are dependent on dopaminergic state. Local field potentials were recorded from the subthalamic nucleus of eight Parkinson's disease patients during temporary lead externalization during surgery for deep brain stimulation. The recordings took place with the patient quietly seated following overnight withdrawal of levodopa and after administration of levodopa. Beta bursts were defined by applying a common amplitude threshold and burst characteristics were compared between the two drug conditions. The amplitude of beta bursts, indicative of the degree of local neural synchronization, progressively increased with burst duration. Treatment with levodopa limited this evolution leading to a relative increase of shorter, lower amplitude bursts. Synchronization, however, was not limited to local neural populations during bursts, but also, when such bursts were cotemporaneous across the hemispheres, was evidenced by bilateral phase synchronization. The probability of beta bursts and the proportion of cotemporaneous bursts were reduced by levodopa. The percentage number of longer beta bursts in a given interval was positively related to motor impairment, while the opposite was true for the percentage number of short duration beta bursts. Importantly, the decrease in burst duration was also correlated with the motor improvement. In conclusion, we demonstrate that long duration beta bursts are associated with an increase in local and interhemispheric synchronization. This may compromise information coding capacity and thereby motor processing. Dopaminergic activity limits this uncontrolled beta synchronization by terminating long duration beta bursts, with positive consequences on network state and motor symptoms.

2021. PLoS Comput Biol, 17(7)e1009116.